Turn me into a cyborg

For context, I was taking a robotics course, and this one lecture on prosthetics initiated some interesting discussion. I had a response in the Piazza page that became longer than I anticipated so I figured I should just turn it into my next blog post.

Couple weeks late, but I just finished watching the prosthetics lecture recording, and there were some good ideas brought up in the discussion that I’d like to bounce off of.

A couple people mentioned that the technology to replace healthy parts with enhanced parts is so far off that there are many other issues to prioritize. I would take this a step further and say that it’s a good thing that the enhancement technology is not available in our generation. There are a couple reasons for this.

1. One scenario that would be problematic is if enhancements were only accessible to people of higher socioeconomic classes. However, there is another scenario that, while more subtle, would also be problematic. If enhancements became readily ubiquitous in our generation (on the level of smartphones and cars), it’s likely that our institutions, looking to increase economic growth, would encourage everyone to have enhancements.

When the status quo adopts ubiquitous enhancements, the technology transforms from a shiny luxury into a manufactured dependency. As a result, the freedom to opt-out of enhancements is choked out. If it is found later that the enhancements have some significant setbacks, or were designed in a way which was not compatible with marginalized groups, it would become very difficult to solve those issues because you’d be resisting the inertia of the false dependency.

2. The narrative of “shiny” enhancements improving daily life would very likely silence out other conversations that are more necessary for the overall well-being of humanity (including making sure people can restore normal functions with prosthetics), which was mentioned by someone else during lecture. Case in point, in the early 2000s Californian citizens voted in strong favor of investing in STEM cell research, but at the same time voted against policies that would strengthen basic healthcare [1]. Or oftentimes, pharmaceutical companies will advertise drugs but neglect to test the drug against the effects of lifestyle changes in exercise and diet, which turn out to be more helpful [2]. AI and space exploration fall in this “hype and shine” narrative as well [3].

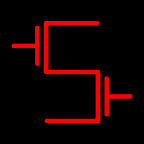

In the specific case of prosthetics, it seems like we can make a distinction between prosthetics that restore and prosthetics that enhance. In lecture, we talked about how the problem of “restoring” prosthetics was how inaccessible the parts could be for amputees who need it, whereas for “enhancing” prosthetics there could potentially be an issue of having the technology be too accessible.

While these two conversations address two different technologies, I think that in the current zeitgeist of STEM culture, it is too easy for the narrative on “restoring” prosthetics to be twisted into a justification for accelerating “enhancing” prosthetics. But as mentioned before, “enhancing” technology is currently not advanced enough to the point where it would blot out the conversation on “restoring”, and hopefully in the future it won’t be an issue at all.

Even if you are not working with prosthetics (I certainly don’t), these themes do translate to other engineering fields to varying degrees. So even if this post is only addressing a very hypothetical and imaginary scenario where enhancement technology is ubiquitous in our generation, it’s still a good conduit for exploring what the core assumptions of STEM culture are.

Citations/Notes

[1] “People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier” by Ruha Benjamin

[2] “Sickening: How Big Pharma Broke American Health Care and How We Can Repair It” by John Abramson

[3] This is not to imply that STEM cell research, medicine, AI, and space travel are bad. In fact, these technologies are brilliant examples of ingenuity, on top of helping plenty of people. The caveat being posited is not towards the technology itself, but instead, how conversations about these technologies undermine other solutions that are necessary, even if those solutions are not “shiny and hype”.

[4] “Race After Technology” by Ruha Benjamin (didn’t cite this one, just a recommendation)